If you’re coming to World of Coffee in Berlin next week, you can meet Marysabel Caballero and Moises Herrera at our booth on Thursday 1pm to 1.30 pm (we’re at at booths V2 and V3 in the Roasters’ Village).

Not in Berlin? London folks will get a chance to meet them at our cupping at Ikawa on June 12th.

Their coffees arrive TODAY at our warehouse in Belgium.

“If you don’t love coffee, you cannot produce great coffee”

Marysabel Caballero

Coffee is in Marysabel Caballero’s blood. Her mother was from a coffee producing family, and Marysabel was a child when her parents quit their city jobs and returned to farming coffee. She remembers life on the farm fondly, she loved helping her parents and spending time with her family.

Marysabel married Moises Herrera in 1996 and together they manage their dry mill Xinacla and about 150 hectares of coffee farms. Marysabel brings a lot of knowledge to the operation, and Moises is the innovator, always asking why things are the way they are and wondering if it can be improved. As Marysabel explains, “I am the tradition, and Moises is the passion.”

Moises came from Guatemala for a job as an accountant, working for a Guatemalan exporter in Honduras. He bought some property and planted coffee as an investment. His plan was to sell the farms and move back to Guatemala when his contract ended. In the meantime, he spent a lot of time in the cupping lab, discovering coffee.

On the day Marysabel and Moises met, he said he would marry her. Marysabel wanted to plant Izote (a plant used at the farm as a fence and to avoid erosion) and was told Moises had some on his farm that he might be willing to sell her. Marysabel didn’t take him too seriously at first, after all he was about to go back to Guatemala. But true to his word he returned to Honduras and two years later they were married.

“There is no such thing as luck in speciality coffee, only hard work”

Marysabel Caballero

Marysabel’s great-grandfather Felipe Garcia started producing coffee in Marcala in 1907. He transported his coffee by donkeys and ox carts from Marcala to the nearest port, in El Salvador. Tragically, Felipe died young, he was only 44 years old. Marysabel’s grandfather, Arsaces Garcia was just nine years old at the time. He married at age 14 and took over the family farm. Marysabel’s mother, Sandra Isabel, is Arsaces 8th child. Sandra and her husband Fabio Caballero bought farmland from Arsaces in 1975. This is where Marysabel’s coffee education began. Marcala was the first Central American region to gain “protected origin denomination” for coffee.

Marysabel and Moises have since earned a reputation as producers of high quality coffee, and have contributed to the growing reputation of Honduras as a specialty producing origin. Everything they do on their farms is documented, and they invest considerable time and resources both in new equipment, and planting of new coffee varieties, in order to improve the quality of the coffee. Taking advice from Tim Wendelboe, they started using raised African beds with shade to dry their micro-lots. After experimenting with a few different types of shade, they settled on a blue plastic (after all, the sky is blue and gives the right amount of light dispersion and heat). They believe drying coffee is one of the most crucial steps. For their larger lots, they dry the newly washed coffee on patios for 6 hours before transferring them to Guardiolas (horizontal dryers) for around 80 hours.

Despite earning early success in Cup Of Excellence, it has not been plain sailing. In 2013 they were hit by a devastating leaf rust attack (known as roya in Spanish), and its impact was felt for years afterwards. In 2015, they came in last place in Cup Of Excellence, which was a turning point for Marysabel. They needed to innovate if they were to get back on their feet. “The first thing you have to change, is your mind,” she tells us. In 2016 she returned to the competition, and not only did she win first place, she also earned the highest per kilo price ever paid for Honduras coffee in the auction.

Sustainability

The Caballeros are extremely committed to the environmental sustainability of their farms. A lot of their energy and focus goes towards improving the soil to ensure a healthy growing environment for their coffee shrubs. On the farms they produce organic fertilizer made from cow and chicken manure mixed with pulp from coffee cherries and other organic material. This is used, in addition to some artificial fertiliser, to ensure that the coffee plants get the nutrients they need. The soil is analysed annually to ensure it provides proper nourishment to the coffee. All water used for processing is filtered before it is released into nature again.

‘If we destroy the environment, we destroy our way of living”

Moises Herrera

They keep some parts of the farms as forest. Moises has seen that deforestation can cause serious issues with water, plus draughts and erosion. He says if we want to keep being able to have fully washed processed coffee, they need to maintain the biodiversity and forest on the farm.

The Caballeros don’t use pesticides on their farms, instead they control the amount of shade to limit the growth of fungus and other coffee diseases. They have also started planting trees further apart than what is considered normal, as this reduces the risk of fungus and leaf rust. Traditionally producers in this area believed that the more coffee you planted, the higher your yields, but the pair discovered that when your trees have more room to grow, they grow healthier and bigger.

Community

Every year the Caballeros choose one employee and help them with whatever is needed, like building them a house. In 2014, they donated land to build a school, La Escuela De La Piedrona.

The local pickers hired to harvest the coffee are paid higher than usual wages, because they are required to sort the cherries during picking. Each picker carries two bags: one bag for ripe coffee cherries, the other for immature and damaged coffee. Marysabel pays great attention to picking, as she believes that the quality of a cherry is at it’s peak when it is picked. Through careful processing they can maintain that quality, but never increase it. Picking at the right time is therefore of utmost importance.

Picker at Marysabel and Moises’ farm. The bag she is putting the cherries into has two parts one for ripe cherries and another part for overripe or under ripe cherries that get picked at the same time. This keeps the cherry and the qualities separated.

It is clear that the selective picking is done to a very high standard at Moises’ and Marysabel’s farms.

They also employ their pickers throughout the season, not only during harvest. They don’t use herbicides, and instead have workers remove weeds by hand. This provides a stable income for workers throughout the year.

Xinacla

Their mill is called Xinacla, spelled the way the indigenous people would spell Chinacla, the name of the town. It’s Marysabel’s small way of honouring them and the land. Xinacla is managed by long-time family friend and colleague Raul, who has worked with Moises for over 23 years. Raul has his own farms and processes the cherry at Moises and Marysabel’s mill, but he says that without Moises he would not work in coffee.

Raul and Marysable at Xinacla

Colour sorter at Xinacla mill

Grading at Xinacla

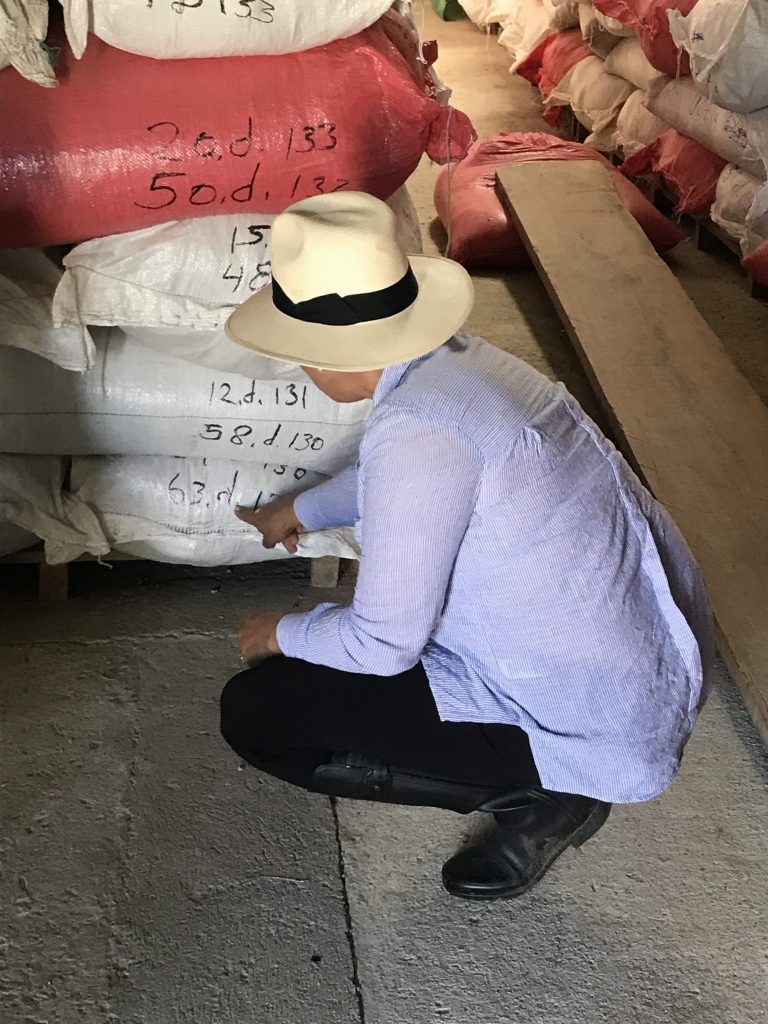

Marysabel explains their system of tracking different lots within the warehouse. This is important for transparency but also very time consuming and tedious. Different lots come into their warehouse and receive an identifying code. By the time samples are approved by buyers, and purchase orders confirmed, many more coffees will have entered the warehouse and been placed on top of that initial lot. So they move all of the bags from the top of the pile to ensure each customer receives exactly what they asked for. It is this attention to detail and commitment to do the hard work that set Marysabel and Moises apart as producers.

Marysabel showing us one of their farms, El Pantanal. Coffee from this farm is frequently our favourite on the cupping table.

0 Comments